"They said New Orleans was ready...evidently not."

Uncovering the story of the players who boycotted the AFL All-Star game in 1965

Twenty-one brothers stepped off the plane at New Orleans International Airport in hopes of sharing the glory of their accomplishments with their peers at the AFL All-Star game. The NFL-AFL wouldn’t merge for another year and at the time, the two leagues were in the throes of a cold war.

The men watched as white passengers, even some of the white players, hailed a cab with ease and took off without a backwards glance. After all, it is 1965. They tried to hail cabs themselves, but were rebuffed by white cabbies. After spending a couple of hours trying, they finally caught a break when they spotted a fellow player (a white man) who helped them get to their hotel by hailing a cab for them.

That experience foreshadowed the type of experience they would have in the Big Easy. This was 10 days after the Tulane Stadium hosted the first completely integrated Sugar Bowl game without incident. But as the AFL players were to find out, incidents abound.

“They told us, bring your wife and kids,” Raiders running back Clem Daniels recalled. “There will also be a golf tournament. It sounded like a big picnic.”

The coming of television in the 1950s marked a new era of American football. In 1958, the National Football League championship game between the Baltimore Colts and New York Giants drew 45 million viewers on NBC. Almost overnight, businessmen from all over the country were ready to purchase new franchises in new markets. The NFL said “no thank you” to most of them, but that didn’t stop Lamar Hunt. The wealthy son of an oil tycoon set out to recruit seven businessmen from cities hungry to form a rival league. The American Football League was publicly welcomed by NFL Commissioner Bert Bell, who said that competition would grow both leagues. But the NFL did not sit idly by and wait for the AFL to gain market share. Instead, it quickly expanded into Hunt’s hometown of Dallas and into Minneapolis, the cities the AFL had designated for a franchise. Shiesty stuff.

The American Football League chose Oakland as a replacement for Minneapolis, as well as Los Angeles, Dallas (for Hunt’s franchise, which moved to Kansas City in 1962), New York, Buffalo, Boston, Denver and Houston as the original eight AFL cities. The league piqued fan interest with an entertaining product on the field, a high-flying aerial brand of football that contrasted with the stingy defenses and running attacks of the older NFL. By 1962, the AFL had drawn 1 million fans to its games. Three years later, the AFL scored a television contract with NBC.

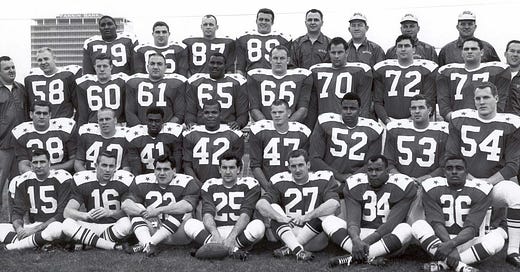

Meanwhile, the city of New Orleans was auditioning to show its potential as a landing spot for an AFL franchise. The All-Star Game presented a big stage for the Big Easy, with nine of the 58 players on the combined East and West rosters becoming future Hall of Famers. A crowd of 60,000, which would have been an AFL attendance record, was expected. But they were off to a very rocky start.

The West team was stationed at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Mid-City, and the East at the Roosevelt downtown, which called for the use of cabs to meet and mingle. But even in town, cab service was spotty. Some black players said that when they did get a taxi, they were driven around in circles, then dropped off miles from their destinations. When they went out, they said, they were denied access at some restaurants and nightclubs in the French Quarter. One player even claimed that a bouncer pulled a gun on him when he tried to enter. That was the last straw. The next morning, a meeting commenced in one of the player’s rooms. Black and white players were deciding whether to play the game. After 45 minutes, the Black players said, ‘Okay, we’re leaving.’ In a show of support, white players such as Hall of Fame Tackle Ron Mix of the San Diego Chargers decided a statement was needed and refused to play. That upped the ante.

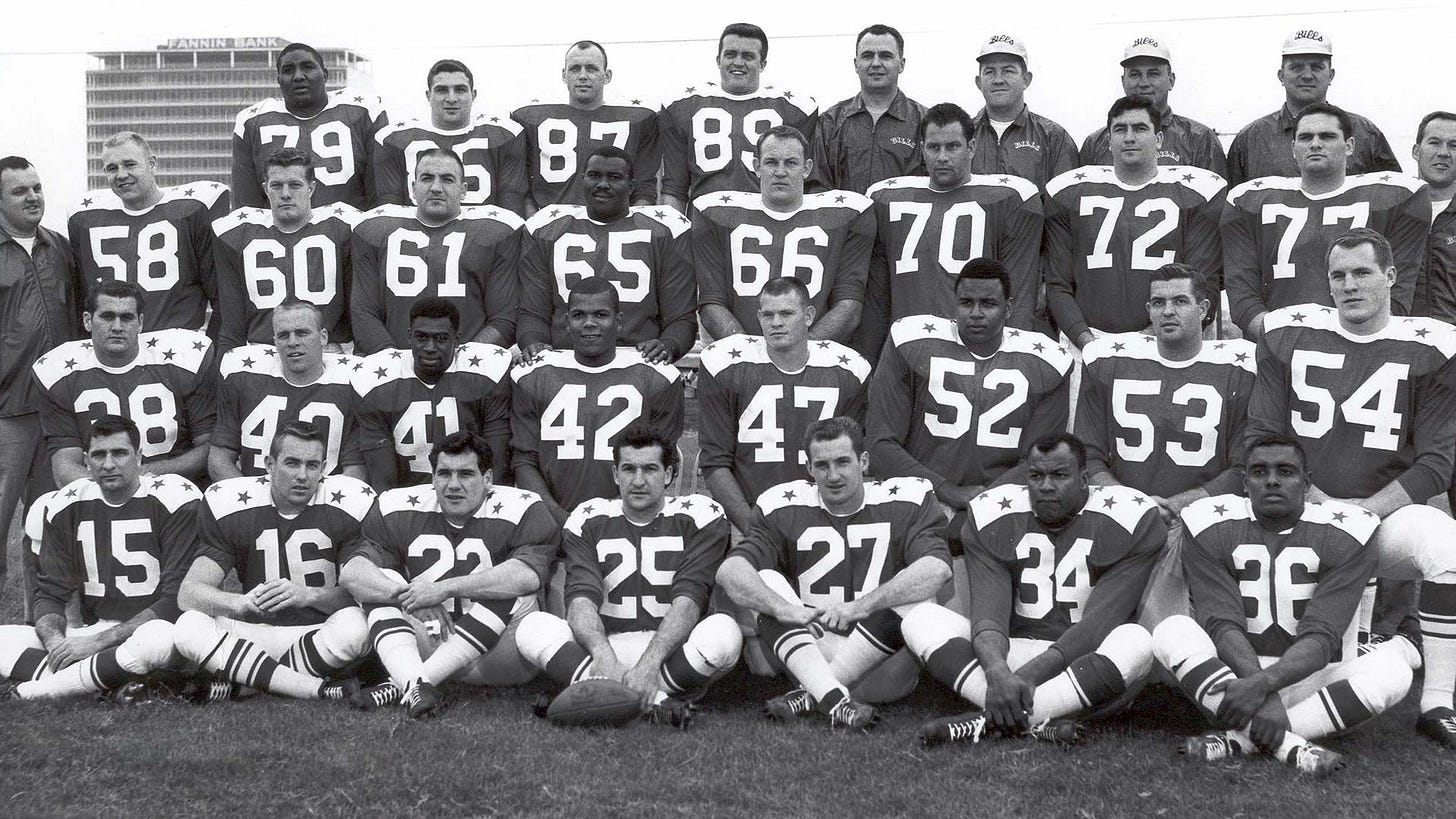

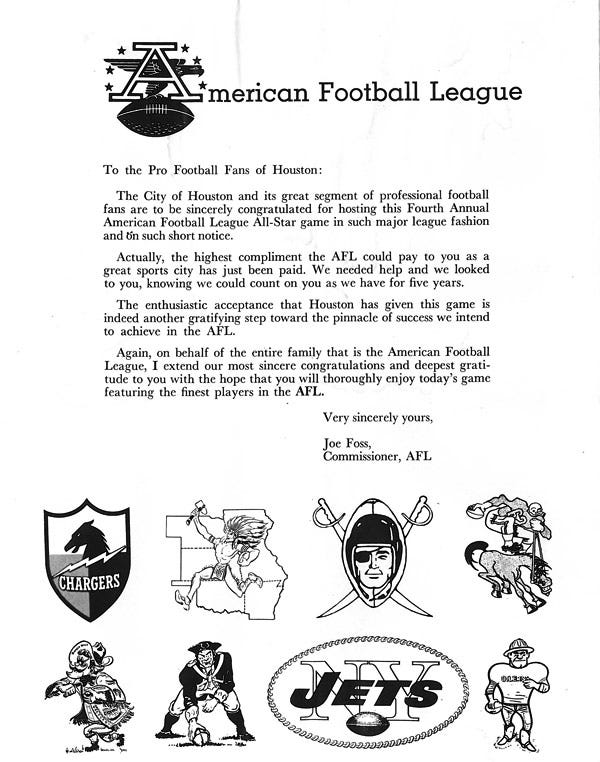

The next day, on Monday, Jan. 11, AFL commissioner Joe Foss announced that the game would be moved to Houston and played at Jeppesen Stadium. Two days later, the teams reassembled in Houston. About 15,446 fans showed up on short notice at the Houston Oilers’ home field, to watch the West stomp all over the East, 38-14. A year later, a NFL-AFL merger agreement announced the new league would be called the NFL and split into the American Football Conference (AFC) and the National Football Conference (NFC).

Over the next two years, the racial climate began to change in New Orleans. Black bus passengers, discovering Black drivers behind the wheel for the first time, no longer had to head to the back of the bus. They could now shop at Canal Street department stores. Restaurants and grocery stores slowly ended the custom of having Black customers go to side windows for service.

The protest transformed the city of New Orleans.