The Syracuse 8

Uncovering the story of courageous student athletes who sacrificed their athletic careers for change in the 1970s

It’s 1970 and it’s not a good time for Black America.

We’d just exited one of the most tumultous decades in American history. The leaders we believed in, the symbols of hope we had were taken away violently & abruptly.

Medgar Evers, assassinated.

MLK, assassinated.

Malcolm X, assassinated.

Bobby Kennedy, assassinated.

America was in a losing war with Vietnam. It was a violent and vicious time.

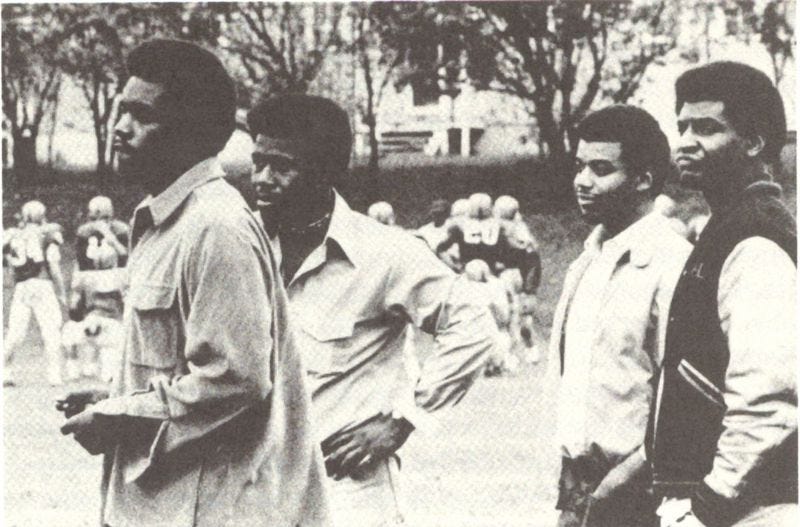

Back at the ranch, Syracuse was a college football powerhouse. They appeared in bowl games and produced many NFL greats. Jim Brown, one of the greatest football players of all time, built his legacy there. Ernie Davis, who became the first African-American to win the Heisman Trophy in 1961, made his bones there. And it would be no different for the Syracuse 8. Gregory Allen, Richard Bulls, John Godbolt, Dana Harrell, John Lobon, Clarence "Bucky" McGill, A. Alif Muhammad, Duane Walker and Ron Womack would change the course of Syracuse University forever.

The Syracuse 8 drafted a petition asking the administration to give Black and white players the same access to tutors and academic advisers. They also wanted better medical care. The team doctor for the team was a gynecologist by training and the recommendation for every injury was ice and rest. The doctor was hesitant to touch Black bodies as well. Another issue was playing time. The big southern schools still weren’t integrated. They wouldn’t play against teams with Black players. Schools north of the “Cotton Curtain” followed unofficial rules about how many Black players could be on the field at the same time. Even at home games. If you have three outstanding wide receivers, you wouldn’t play them all together because you didn't want the big money boosters to accuse the program of going ‘Black’.

The last straw: the group had called for a more diverse coaching staff for over a year. Black players hoped that a Black assistant coach would afford them the opportunity to vent their grievances to someone who understood their plight. Instead, former SU great Floyd Little, then of the Denver Broncos, was brought to Syracuse for two days of practice in April to essentially pose as a Black coach.

“The misrepresentation of Mr. Little as the black coach,” the players would argue in a statement, “was a breach of promise made to us. Thus, we initiated a boycott of spring practice.”

The media got a hold on the narrative and began labeling the Syracuse 8 as "Black dissidents" or "Black militants" or sometimes just "the Blacks." The Syracuse 8 were suspended from the team. Some of their white teammates threatened to boycott if the Black players were allowed back. The chancellor’s office was flooded with letters from alumni, wanting them off them off the team. They wanted their scholarships revoked and out of Syracuse University. Some of the fans threatened to boycott the games if they were ever allowed to come back. The players went home for the summer, not knowing what would come of their protest. Over the summer, Jim Brown stepped in to help as a mediator between the players and Coach Schwartzwalder. It didn't work.

Syracuse Chancellor John Corbally forced head coach Ben Schwartzwalder to hire a Black assistant coach, and that fall he did. But he wasn’t listed as a coach in the program. Corbally also sent a statement to the athletes which he required them to sign before they would be allowed to return to the team. The players thought the document was demeaning and sensed resentment from their white teammates.

“These people have broken every principle that football stands for,” a white player told the Post-Standard before the season opener against Kansas. “They have knocked the team.”

They promptly rejected reinstatement and continued their boycott. They sat out the whole season. Only Gregory Allen and John Lobon would ever again play for SU again.

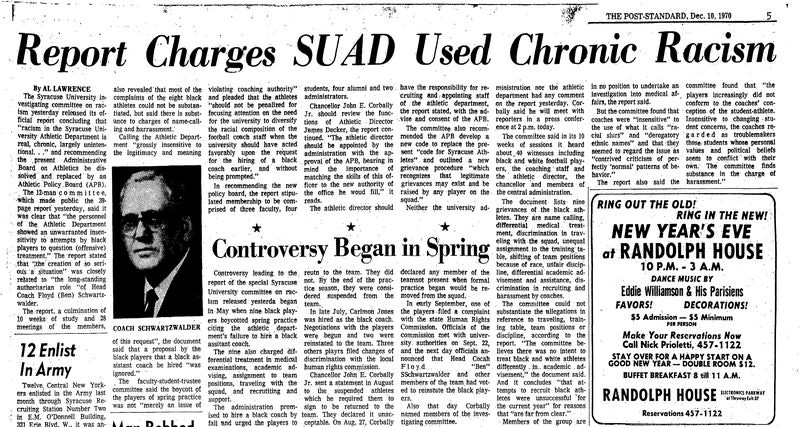

After the season, Syracuse University created a committee to investigate its athletic department. After a 10-week study, the committee concluded that “racism in the Syracuse University Athletic Department is real chronic, largely unintentional, and sustained and complicated unwittingly by many modes of behavior common in American athletics and longstanding at Syracuse University.”

The 39-page report released on Dec. 9, 1970 found that the “Athletic Department showed an unwarranted insensitivity to attempts by black players to question (offensive) treatment,” and criticized the “long-standing authoritarian role of Head Coach Schwartzwalder.”

The Syracuse 8 kept their scholarships and were allowed to graduate. Of the nine, eight graduated from Syracuse University. Four went on to earn master’s degrees. In 2006, the Syracuse 8 were invited back to receive the Chancellor’s Medal — the university’s highest honor — and their letterman’s jackets.

It took 36 years for Syracuse to apologize and recognize the players were on the right side of history.