Before Jackie, There Was Moses

Uncovering the story of the first Black man to integrate Major League Baseball not named Robinson

Disclaimer: I love Jackie.

We love Jackie.

Jackie Robinson represents a symbol of progress and forward movement. His courage and determination to integrate baseball opened the floodgates for Black and Brown players alike. But that monumental moment on April 15th, 1947 came nearly 63 years after Major League Baseball's color barrier was really broken.

Have you heard of a man named Moses?

Not the one in the Bible.

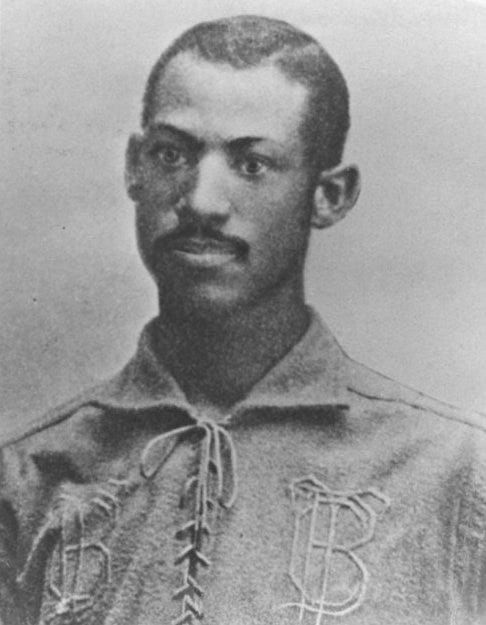

But Moses Fleetwood Walker, a Michigan grad and catcher for the Toledo Blue Stockings, who is actually the first African-American to play in Major League Baseball?

Walker rose through the collegiate ranks after transferring from Oberlin College to the University of Michigan in 1882 and experienced immediate success. Walker batted .308 for the Wolverines and helped lead the team to a 10-3 record. After finishing his career in Ann Arbor, Walker signed with the minor league team, the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League in 1883.

Moses scratched and clawed his way to the professional ranks, and caught a big break at the beginning of the 1884 season. The American Association (which would later become the modern-day American League) was formed. One of the American Association's first moves was to add the Toledo Blue Stockings to its list of participating franchises. On May 1, 1884, against the Louisville Eclipse, Moses Fleetwood Walker took the field, and officially broke the color barrier of Major League Baseball.

Walker would go on to have the worst game of his career on the day he integrated baseball, going hitless in four at-bats and committing four errors. Over time though, his play improved, and Walker proved himself to be a solid contributor for the Blue Stockings. In his time as the starting catcher for the Blue Stockings, Walker batted .264 (which was well above the league average in this pitching-dominated time period) and scored 23 runs.

He did all this while enduring the constant racial slurs and death threats. Before a game in Richmond, Toledo’s manager, Charlie Morton, received a letter declaring that a lynch mob of 75 men would attack Walker if he tried to take the field in the former Confederate capital. Walker didn’t make the trip to Virginia. Moses also dealt with issues with his teammates. Walker's teammate with the Blue Stockings, pitcher Tony Mullane said (Moses) “was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals.”

After playing in 42 games in 1884, Walker suffered a season-ending injury and it was the last time he ever played Major League Baseball. The Toledo Blue Stockings folded in 1885 and Walker bounced around different minor league teams until 1888. In 1889, the American Association and the National League "unofficially" banned African-American players, allowing for Major League Baseball to fall in line with the Jim Crow laws.

Life after pro baseball took a turn for the worst for Moses.

Walker took a job in Syracuse handling registered letters on the New York Central Railroad. In 1891, Walker stabbed to death an ex-convict named Patrick Murray outside a Syracuse saloon. He argued that he had acted in self-defense after being struck in the head by a rock by one of his white attackers.

The trial itself was a mess. The prosecution maintained Murray only wanted to shake Walker's hand. Murray’s cronies all swore under oath it was true, and they tried to prove Walker was drunk. The trial boiled down to Walker himself, who took the stand. He recounted how he had been searching for Simmons throughout the Seventh Ward, before he stopped to have a few beers with a friend. A couple of hours later, Walker said, he walked past the group of men on the street corner. He testified the men asked why he was in their neighborhood. The exchange became increasingly hostile. He said one of the men accused him of putting on airs "for a damn nigger." The men said Walker cursed them. Walker said he left.

"I turned across the street when I was hit in the back of the head with a stone, " Walker testified. He said he turned to defend himself, and was charged by two attackers coming off the barroom stoop. One held something in his hand. Walker drew his knife and struck. Amazingly, an all-white jury acquitted Walker of second-degree murder.

Following the trial, Walker moved with his family to Steubenville, Ohio, where he found work as a mail clerk. While on the job, he was arrested for mail robbery and served a year in jail. By the turn of the 20th century, Walker was a theater owner in Ohio, where he received patents for his work in early motion picture technology.

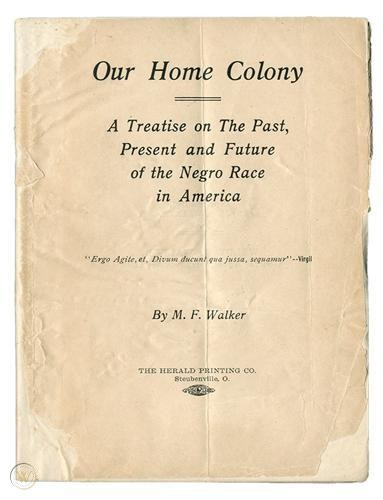

One patent helped film projectionists determine more efficiently when a reel was ending. With his younger brother, he briefly edited The Equator, a newspaper that focused on race matters and offered a service to help Blacks emigrate to Liberia. In 1908, Walker published a book titled Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America. In it, Walker argued that whites and Blacks could never peacefully co-exist in the United States and urged Blacks to return to Africa.

Moses Fleetwood Walker died in 1925.